Randel Washburne

Copyright 2007

South

Queen Charlotte Islands

We were in Seattle this morning. At late afternoon Tom and I

stand on a rocky beach on South Moresby Island, near where the tip of the Queen

Charlotte Islands archipelago dead-ends into the empty Pacific. The sound of

our last link to civilization echoes and then fades over the mountain pass to

the north, leaving the lap of waves on our gravel beach and the freshening

breeze sighing through the trees. Clouds scud just overhead, suggesting that

today’s showers would soon resume.

Welcome to the Queen Charlotte Islands of 1974, before the

national park and before “Haida Gwaii” and “Gwaii Haanas” had meaning to anyone

but speakers of the Haida language. In those days the Haida people seemed

inclined to ignore their long-abandoned ancestral villages on the remote south

islands along with the memories of decline and smallpox decimation, and showed

little interest in protecting their spectacular carved cedar monuments there.

For a century these totems and house posts had remained there alone to decay

naturally, and hardly anyone went there to disturb them.

Though it seemed to us the edge of the known world on

arriving, getting to the south Charlottes was easy if you had a folding

kayak – simply book a couple of seats on

the daily jet from Vancouver and charter a floatplane to take you the remaining

fifty miles to the southern end of the archipelago. There wasn’t even an

airline baggage charge for our large pile of boat parts and camping gear.

By 1 pm we unloaded into drizzle at Sandspit airport in the

central Charlottes. This had been constructed as a major military base during

the war, and its acres of concrete were now lightly used. In the little

terminal we were told that our Beaver floatplane was standing by, but that our

flight was on hold due to low visibility. There was nothing to do but wait.

So we walked, passing the home of Neil and Betty Carey just

outside the airport entrance. Their recent article in Alaska Magazine was why we were here. These expatriate Americans

were the chroniclers of the south Charlottes, having explored extensively in

small boats. My last summer’s adventure kayaking West Chichigoff Island in

Alaska had hooked me on more of the same, and Neil Carey’s pictures and

descriptions of the lush forests and abandoned Haida villages in the south

Charlottes were all that Tom, another graduate student, and I needed to decide

to go there.

We collected nautical charts and researched the history of

the remote Haida villages, including a visit to Bill Holm, the foremost authority

on Haida art history at the university’s Burke Museum. He had actually been

there. He led me to an article on the village of Ninstints, part of which is

quoted later. We also wrote to the Careys for any advice they could offer. We

received no reply – perhaps one of many inquiries from people longer on

ambition than execution.

Returning to the terminal, the charter people, perhaps

tiring of our pile of duffel in front of their desk, announced that conditions

were now marginally suitable to fly. A forklift was summoned, our gear was

loaded onto a pallet, and we followed it out to our aircraft. The Beaver is a

fair sized aircraft, capable of taking much more than the two of us and our

equipment. Standing on its pontoons and below that, the retractable landing

gear, the Beaver’s flight deck was nearly eight feet up, hence the advantage of

the forklift.

Loaded up, we were ready. Tom climbed into the right seat,

and I went into the back with our bags. The engine started up and without

delay, we taxied away. We rolled across concrete aprons and taxiways toward a

huge ramp that had served wartime PBY’s coming and going from the sea. I had

expected that we would likewise trundle down it, but before we got there, the

pilot gave it the gas and we lifted off.

Conditions were truly barely suitable for flying. The cloud

deck was several hundred feet above sea level, or less, so we cruised along

just below or sometimes briefly in it. Rain squalls pounded the windscreen

regularly, and we gently bounced and rocked in the eddies and swirls of the

southerly wind. I watched my map carefully, eager to observe and remember

landmarks for later. One in particular I remember – a singular and romantically

named offshore pinnacle that I had tried to visualize poring over my charts.

“All Alone Stone!” I exclaimed, and the pilot nodded.

We grumbled southward for a half hour, the pilot pointing

out features here and there – Hot Springs Island, with a cabin and soaking

pools, and logging camps on the bigger islands. The loggers were gradually

stripping their way south. He showed us Dolomite Narrows, which would be our

closest source of help should we need it – just a few squatters (“hippies”)

living there. We glimpsed a shake roof or two through the trees.

Now he advanced the throttle and we climbed toward a gap in

the mountains that separated us from our destination at the south end of

Moresby Island. Over the misty pass and then a long glide down to Liscombe

Inlet ahead, gray and specked white from the wind off the open ocean to the

south. Down to a few feet above the waves, we flew on toward a low island ahead

as the pilot told us he would set us down in the little bay in the lee of the

island. We settled into the quiet water there and idled toward the beach.

“One of you is going to have to wade and hold me off the

beach.” The pilot wasn’t getting out. I took off my boots, rolled my pants to

the knees, and climbed down to the pontoon as the engine stopped, and then

dropped into the icy water – a shock, but I was glad for the numbing of my feet

since the barnacled gravel wasn’t comfortable. I pulled a pontoon in as close

as possible without grounding it, and Tom leapt for the beach. The pilot

started handing bags to me, and I became very busy, since my job was both to

pass them to Tom and simultaneously hold the large, heavy aircraft in position

against the offshore wind. Soon it was done and I was directed to turn the

plane to face seaward. After reassuring us that he’d keep an eye out for us,

the pilot closed the door, started up, and was gone.

In my mental preview, I had looked forward to this very

moment, but listening to our only link to humankind fade to nothing sent a cold

chill down the back of my neck. We had no radio, and just a couple of flares

for use in the off chance we might see a boat or a plane, both of which were

unlikely in this out-of-the-way coast. So if we get stranded, sick, or hurt and

can’t deal with it on our own, we are screwed.

Which raised the first burning question: do we have a

workable boat? This was a more vital question than it was at the beginning of

last year’s Alaska trip where we assembled the kayak in the city of Sitka.

Here, if we’d forgotten something or a part had been broken in transit, there would

be no running to the hardware store to fix it. As we opened our boat bags to

find out, another rain shower commenced and the scrubby treetops to windward

seemed to dance a little harder.

The boat went together as it was supposed to. It was the same

as I’d used in Alaska – a double Folbot with a big plywood rudder and single

large cockpit covered by a spray skirt with zip-up closures for each of us. Our

gear was either stuffed ahead of Tom’s feet in the front position or behind me

in the rear one. Narrower duffel went along each side of us, so that we

squeezed into confined but comfortable seats.

Ready to go, we zipped up extra tight as the rain continued,

knowing the calm of our bay in the lee would cease as we rounded the island

into the open inlet to the south. It was a poor day for paddling and we were

barely able to make headway against the wind. We managed four miles down the

west shore of the inlet before finding a quiet, pretty cove. Behind a smooth

gravel beach was a carpet of moss under Sitka spruces making for a very

comfortable camp.

The rain ceased after dinner and the seas on the inlet died

to calm. A seal, apparently inexperienced with humans, curiously swam toward us

until he frightened himself, dove in a panic, surfaced to seaward, to repeat

again and again.

The next morning was beautifully clear and we headed for

Anthony Island, site of the Haida village of Ninstints, which contained the

most and best-preserved totems. (These place names have since been replaced

with the longer and more complex Haida ones, but I’ll continue with those used

at the time.)

The Haida abandoned this village about the time my

grandfather was born. For about a hundred years the totems here had withstood

storms, rot, thieves, and vandals. Though the best of them were removed in 1957

for display in the Provincial Museum in Victoria, those that remained were

totally vulnerable. We felt a heavy responsibility about that. Today the Haida Gwaii

Watchmen program looks out for this and other sites in the Charlottes,

restraining visitors to gravel paths and interpreting the totems and house

pits.

We camped four days on the beach directly in front of the

village, sometimes peeking over our shoulders at the stern characters that

seemed to glare down disapprovingly. I photographed and sketched, wandering

around the multi-tiered house pits, and discovering nearly hidden wonders, like

a small carved frog on a fallen totem nearly covered with moss in the brush. As

I noted in my journal, “something, either a totem or a house post, is visible everywhere

around here.” On the beach we found bits of what seemed to be European

crockery, and we wondered about its history.

Important and tragic events did occur here in the early

years of the Haida’s contact with Whites.

The following was taken from “Anthony Island, a Home to the

Haidas”, Report to the Provincial Museum by William Duff and Michael Kew,

Victoria, BC, about 1960. Duff and Kew were involved in removing the totems and

surveying the village in 1957, and compiled their account from a variety of

historical sources.

The Haida at Ninstints had been trading with English ships

since about 1787, primarily for furs. The village was known as Koyah’s village,

for its chief. Trading with Koyah and his people was friendly, especially with

Captain Robert Gray in the Lady Washington (the replica of which is a common

sight in northwest coastal waters today).

In 1791 the Lady Washington returned, now under the command

of John Kendrick. When Koyah and others came on board, petty pilfering occurred

(as it often did), but when his laundry hanging out to dry was taken, it was

too much for Kendrick. He ordered Koyah’s leg to be clamped in a cannon mount

and held him there until all of the stolen items were returned and all the furs

ashore were brought out and purchased for the price he thought was right. Then

the chief was released and the ship quickly departed.

What

Kendrick regarded as a simple “lesson” must to Koyah have been a monstrous and

shattering indignity. No Coast Indian chief could endure even the slightest

insult without taking steps immediately to restore his damaged prestige. To be

taken captive, even by a white man, was like being made a slave, and that

stigma could be removed only by the greatest feats of revenge or distributions

of wealth. This humiliating violation of Koyah’s person must have been

shattering to his prestige in the tribe.

Unwisely, Kendrick returned to Ninstints just three days

later! Trading seemed to resume normally but after fifty Haida had boarded the

ship, Koyah and the villagers took control and forced the crew below.

Unfortunately for him, Koyah delayed in taking further action beyond taunting

Kendrick. The crew had time to collect firearms and other weapons and retook

the ship, slaughtering forty to sixty Haida either on deck or as they fled in

canoes, without any injuries of their own.

The effect

on Koyah’s prestige of the second defeat can only be surmised. Like the hero of

a Greek tragedy, he was pitted against forces stronger than his own, but he had

to continue the struggle…And struggle he did. For one thing, he immediately

went to war against Chief Skidegate’s tribe. Then, during the next four years,

he attacked three more ships. Twice he was successful, overpowering and killing

the crews. The third time, however, his attack was repulsed and he himself was

killed. This record of four attacks – two successful and two disastrous –

established Koyah as the most warlike chief on the whole coast at this time…No

other chief succeeded in capturing more than one ship, and his successes

probably encouraged others to make similar attempts. His failures fanned the

hatred on both sides.

The authors point out that there are several conflicting and

inconsistent additions to the account from other sources, so exactly what

happened may never be known. The results, however, were tragically clear.

Unlike chiefs in the other villages that continue to bear their name, Koyah’s

lineage and name faded and the village became known by the name of one of its

last lineages of chiefs, Ninstints. The population on Anthony Island declined

steadily and then precipitously with the widespread smallpox epidemic of 1862

and others that followed. By the 1880’s the last permanent residents moved to

Skidegate.

Having read about these events beforehand, camping at

Ninstints, though fascinating, was not comfortable for me. All the sadness and

rancor that had happened here was never far from my mind, always with the

brooding totems watching us as a reminder.

We explored the rest of Anthony Island, including a

circumnavigation and returning several times to a little cove on the south end.

It had a spectacular view south along Kunghit Island to Cape St. James, and was

surrounded by very rugged rocks. On top of these were auklet burrows, smelling

strongly of fish.

We also tried a little foraging to spice up our mundane

dried cuisine. I made a crab trap out of two bows of cedar branches, covered

with a piece of derelict net, and joined in the middle so it would fold in half

when pulled up, trapping the crabs feeding on the clam bait in the middle. We

took it out to the center of the cove in the morning and returned to harvest

our catch in the afternoon. It was incredibly heavy to pull up, but instead of

a seething mass of crabs, there was only a fat multi-armed starfish enjoying

the bait. So much for crabbing.

After four days at Ninstints we moved on to Rose Harbour.

This was the site of a whaling station that operated from the turn of the

century until 1940, and now uninhabited. It was a beautiful but sad place –

lots of derelict buildings, whalebone, harpoon heads, and big boilers for

rendering the blubber. The bugs were awful. Rose Harbour is a lot different

today, with a lodge, restaurant, and kayak rentals and guides.

The next morning we went on north and around the peninsula

into Skincuttle Inlet. We made 20 miles due to calm seas and a light following

wind. I had made a little 2 by 4 foot square sail that had a pocket to fit over

a paddle blade. We took turns holding the “mast” aloft while the other paddled.

The high point was sailing around Benjamin Point while we ate lunch. Crossing

Carpenter Bay we clocked ourselves at four knots – very good for our boat.

We pulled into Jedway for the night – an abandoned open-pit

mine, “a forsaken gravel heap” as I described it, but a fair campsite. In the

evening I hiked up the road to the open pit area where I was able to see east

over Ikeda Cove and west over Skincuttle Inlet.

In the morning we crossed the inlet to Burnaby Island, and

spotted some huts on the beach in Swan Bay. On going ashore I was introduced to

a way of life that would leave a lasting impression on me for many years and

strongly affect the meaning of sea kayaking for me.

Tom and Tory lived in cabins they had built from driftwood

and cedar shakes scavenged from the beach. They were squatters – just one of

many back-to-the-land young people from many nations who took advantage of the

BC government’s liaise-faire management (seemingly none at all) along the

rainforest coast. These people formed dispersed communities in places like

Florencia Bay and Flores Island near Tofino on Vancouver Island, and the east

side of Moresby Island in the Charlottes. We would meet many of them in the

next week.

Though this couple lived in Swan Bay alone, they were only a

few miles from others like them in Dolomite Narrows. That was a good thing since

Tory was expecting a baby in just a few days. The local acupuncturist from

Dolomite Narrows would come to assist and had already delivered several

children there.

We stayed 24 hours at Swan Bay, learning about how they

lived. They had arrived in an 18-foot sailing canoe (carrying about 1,500

pounds of supplies initially), which they kept anchored in the bay. Occasional

shopping trips were made in the canoe. It took about four traveling days to

Moresby Landing where they could get a ride to Queen Charlotte City.

Their houses were pentagonal and had a small sleeping loft.

They were covered with cedar shakes split from logs on the beach. As is common

on beaches not exposed to open sea, small driftwood for fuel was limited, so

they burned green alder cut from nearby trees in their wood stove, which seemed

to work ok.

We learned about foraging, going with Tom to collect salad

greens off the lushly covered nurse logs in the forest. These included

chickweed, cleaver, and “pineapple weed”, which may have been chamomile. I

still have samples of all these pressed in my journal. They also collected

small spruce buds, the inside of a thistle (like celery) and stinging nettles

rendered harmless and delicious by steaming. We also tried what the Haida call

“gau” – dried ribbon kelp that spawning fish had covered with roe. Toasted a

little it was like excellent potato chips. It was illegal for Whites to harvest

it, mainly because the Japanese would love to import all of it.

Tom and Tory were not meat-eaters, but due to her advanced

pregnancy, Tory was having a strong craving for it. Three or four Sitka deer

were frequently hanging around their cabin, munching on the downed alder leaves

or sometimes just staring in through the door. Tom had a .22 rifle he had never

fired, but this morning he had been thinking that if the deer showed up, he was

going to shoot one. When they arrived,

he took it as a sign it was meant to be, and loaded the rifle while Tory

sharpened the butcher knife, watched by a buck just a few feet outside the

door. He couldn’t miss with a shot

between the eyes and the buck dropped like a rock. The others gave a start, and

then went to see why their colleague had suddenly decided on a nap. Soon they

were back to browsing while we hung up the carcass for butchering.

As soon as we started, their cat went wild, yowling and

rubbing on our legs. Tom saved the heart and liver, figuring the latter would

be particularly good for Tory. But the heart promptly vanished, stolen by the

cat. We had an excellent stew that night, and they gave us a forequarter which

we carried and finished over the next several days. We gave them some candy

bars and a book.

About noon the next day we departed for Dolomite Narrows and

north. Tom marked out several good cabins that we could use along the way if

not occupied.

So what became of Tom and Tory? Sixteen years later this

clue emerged in the Burnett Bay cabin journals, written by a prominent and very

well traveled kayak designer who had been to the Charlottes at some point after

us:

August

2000 …There used to be another wonderful gazebo-shaped cabin at Swan Bay in the

Charlottes …the woman who raised three or four children in this cabin now has

had the distinction somewhat to the effect of being the leading Winnebago sales

person in the US…

Coming into Dolomite Narrows we encountered two women and

some children picking glasswort. Also known as beach asparagus, it is crisp and

a bit salty, and very good either raw or cooked. They canned it for later.

There were a half-dozen or so cabins here for several families and assorted

single people that came and went. The local acupuncturist/astrologer was also

building a 25-foot dory out of chain-sawn red- and Alaska cedar. It looked

rough, but impressive given the circumstances.

After lunch we set out for our next destination – Hot

Springs Island. It was about fifteen miles north, so this would be a long day.

The weather was beautiful – sunny and a light west wind. Our next question was

how to cross Juan Perez Sound, the shortest crossing was five miles, but out of

our way. The most direct route was seven miles of open water, and we opted for

that. This route would also take us past my object of curiosity – All Alone

Stone.

The wind was quartering off our stern, so we raised the

sail. I had now made a mast, which held the sail a little higher and allowed us

both to paddle. It took only about a half hour to cover the two miles to All

Alone Stone. No place for a break here – it was only a hundred yards long and

very steep, sitting miles from anything else. We went on toward Ramsey Island.

The wind now freshened considerably and the seas built to three feet. I shipped

several of them over my lap and got wet as water leaked through the skirt

zipper. We made Ramsey Island at 6:30 pm, completing the 6 ½ mile distance in

an hour and a half – over four knots!

Not bad for a long haul.

We arrived soon after at Hot Springs Island, totally beat.

It was worth it. There was a bathhouse with a tub and two pipes: lukewarm and

very hot. You could get just what you wanted by adjusting the two. The only

problem was that we couldn’t find any water that wasn’t sulfurous, so in the

morning we paddled back to Ramsey with aching arms to get some. The rest of the

day was relaxation in the sun. We gathered goosetongue (seaside plantain) and

glasswort, fried up some of our venison and poured onion gravy over it, served

with steamed glasswort, which was like string beans, but better! Had that with

a goosetongue, thistle, and chickweed salad seasoned with reconstituted minced

onions and vinegar and oil. Desert followed – chocolate pudding, brandy, and

coffee. The best dinner ever.

We spent two nights at Hot Springs, resting, observing, and

fantasizing about the lifestyles we seen in this beautiful place. In the early

afternoon four fishing boats arrived with eight people to take baths. We were

already packing up and left by mid afternoon. The fishing boats passed us later

and swung in close for a look – kayaks were still a unique sight.

Camped that night at Gogit Point on Lyell Island – a

fantastic spot with plenty of dry moss to lounge on. Walking south from the

campsite I found a canoe drag-way, where the rocks had been moved aside all the

way down to the low tide line. We figured the Haida parked their canoes here

rather than in front of the obvious camp area where the tide flat was much

longer.

Had another dinner extravaganza of the remaining venison,

dried oxtail soup, glasswort, and goosetongue. Made banana bread in two pans in

the coals for desert.

The next morning was intermittent rain with a southeast

wind, and we had a nice ten-mile paddle-sail up to Kunga Island. On the way two

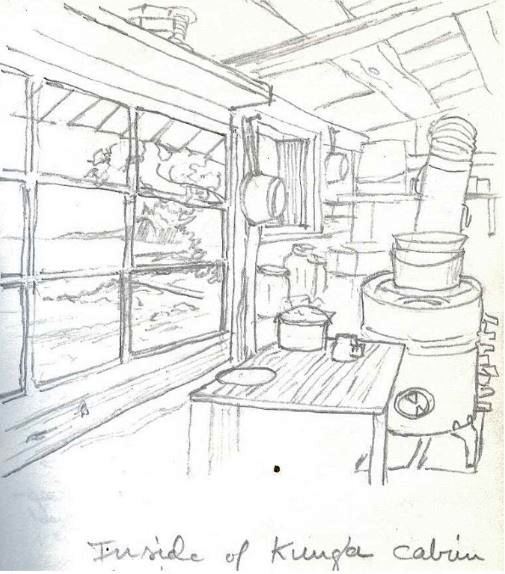

seaplanes buzzed us, but not our Beaver. We were heading for Kunga cabin, a

neat, tiny structure whose builder and sole occupant was somewhere else. The 8

by 10 floor area was just big enough for Tom on the single bunk and me on the

floor next to the wood stove.

The next morning we went directly across the channel to Tanu

village site, now another Haida Gwaii Watchmen location. There were no totems

here, but there was a well-preserved house pit with the two-level sleeping

shelves around the edges, and one standing house post with a beam still in the

mortise at one end.

Walking south, I found a gravestone on a little hill,

inscribed only with “In Memory of Charlie” and two shaking hands. Really

touched me somehow. There were signs that this and other graves nearby had been

dug up at some point.

As I sat looking at the stone, I saw a river otter about

twenty feet away. He was lying on his back on the moss, wriggling and chuffing

as he dried and scratched his back. Then he got up, shook, and trundled back to

the beach. A very strangely shaped animal ashore.

One of the pleasures of kayak trips, especially in the early

days, was that rounding the next point may bring the totally unexpected. So it

was, as we crossed to Louise Island and entered Thurston Harbour. It was a

logging camp. I’m not sure why we decided to stop there – a group of trailers

and mobile metal buildings surrounded by dismal clearcuts, and marked with a

sign “Thurston Harbour Tree Farm”. We tied up at the float in late afternoon

and were met by two off-duty loggers, Dave and Jeremy, who told us we were just

in time for dinner.

We followed them to the cookhouse where we were welcomed

with a sumptuous dinner. I don’t remember what it was other than that my

journal reported its excellence and that there was apple pie for desert. Then,

most welcome of all, we took showers in the bunkhouse. Dave and Jeremy took us

to the beer hall for warm suds, which didn’t impress us very much. The

friendliness and generosity of these people certainly did.

Following the beers, we bad farewell and paddled on in a

glassy calm evening through a beautiful sunset, heading for Vertical Point

which was about six miles distant, and arrived at dark.

There was a cabin here that Tom at Swan Bay had told us

about – a tiny “houselet” built by an artist named Benita who spent most of her

time somewhere else. Benita’s house was six by eight feet, with a screened

porch about the same size. Built from dimension lumber, it contained a stove,

single bed, and table or additional bed on the adjacent wall and overlapping

the bed – just enough room for the two of us.

There were two people already camped at Vertical Point when

we arrived, though not using the cabin. They were also in a kayak and lived

like Tom and Tory in a cabin elsewhere on Burnaby Island to the south. They

were returning from a shopping trip in Queen Charlotte City. He was Renye,

which I’ve doubtlessly misspelled, a French-Canadian from James Bay. She was

Adriatique, originally from Argentina. She was in her third trimester of

pregnancy.

As we arrived and carried up our boat and gear, Renye warned

us that the biggest spring tide of the year would occur that night. I stowed

the boat on some ancient drift logs at the back of the beach that appeared to

have been there forever, laid the paddles across the cockpit, and went off to

bed.

We awoke to find the little cove completely dry, that all of

the logs on the beach had been rearranged, and that our boat was vanished.

Renye shook his head – we had been warned. We stood in shock. What now? With no

radio we’d have to wait here until a fishing boat happened by, or for Renye to

pass the word to someone, hopefully before Fall. My humiliation was complete.

But then – oh joy! We saw it lodged on a point about a

half-mile away where it had grounded on the falling tide at the last point

before floating out into Hecate Strait. Had there been any wind last night it

surely would have been long gone.

I took this lesson to heart, and except when parking my boat

in the forest, always tied it securely on the back logs regardless of springs

or neaps. But it did happen again, though in a different way, which a short

digression will explain.

Years later, during my era of exemplary kayaking author and

instructor, I made a solo trip to Vancouver Island’s Broken Group in January,

my preferred time of year out there. I landed in the south cove at Clark

Island, one island in from the group’s Pacific fringe. Pulling up the bow as

far as I could without unloading, I walked up the beach to decide on where to

camp, here by the old chimney or out on the point. After perhaps a minute I

decided on the point, and turned to move the boat down the beach. But it was

now a hundred feet off the beach and rapidly heading for Coaster Channel in the

light breeze. Take heed: in the winter the huge Pacific swells can create a local

surge, like a mini-tsunami, not a wave, just a steady, silent rise in water

level across the whole cove, with an equal fall and backflow to follow. Later I

watched it happen again, and saw the sea rise several feet and then fall again

over the period of about a minute.

I was ashore with nothing. I usually carry up my “purse” – a

small dry bag with emergency materials such as fire starter, multi-purpose

tool, and a Space Blanket, along with wallet, car keys, etc. Not this time – it

was still sitting in the cockpit. I was wearing my rubber knee-boots, quick

drying pants, pile tops and paddle jacket, spray skirt, PFD, and Gore-Tex hat.

I would have been marooned here for at least three days, the time I did stay,

and saw no one.

So I waded and then swam until I could grab the bow toggle

and tow it back to the beach. I wasn’t really cold from it, and after dumping

the water out of my boots most of my clothes were dry by the time I had

unloaded and the camp set up with my wood stove going in the tent. It certainly

could have been far worse with my lack of immersion protection (that’s another

story) if I had turned to look after the boat a minute or two later. At what

point would I have decided not to swim for it?

Anyhow, back to 1974’s Lesson One. We trudged around the

cove and out to the point to retrieve our ill-deserved gift from the sea. As

expected, there were no paddles in sight. So we took up pieces of driftwood and

went out through the extensive kelp beds to look for them. The varnished shaft

and blades blended perfectly with the kelp fronds and hoses. Still, we found

one of them. The other was gone forever.

We returned to Vertical Point. Renye had been taking

advantage of the minus tide to catch an octopus. About then a woman named Becky

arrived in a kayak. She lived in Queen Charlotte City and was traveling solo to

visit friends in the community around Burnaby Island. Becky expertly pounded

the skinned tentacles on a log with the back of her axe and then fried them up

for us all in soy sauce and butter. Outstanding, and not tough or rubbery as is

its reputation.

Later in the morning when the tide came up, Renye and

Adriatique loaded up and headed on to their cabin. As the picture shows, the

boat was heavily laden and for this trip Renye had come all the way south with

his feet on deck, since he was carrying a French horn he had purchased in the

cockpit. One may scoff, but they had been surviving down here for several

years, and knew to adjust when and by what route they paddled. I had nothing

but admiration for them.

I set to work making a new paddle out of a piece of spruce

and a cedar shake, both off the beach. I wired and taped the cedar blade in

place. The result was so light and effective that we both vied for a chance to

use it on the way to Sandspit, where I sawed it in half to take home for a

keepsake and reminder about spring tides.

At the next morning’s minus tide I searched around for

another octopus without luck. We settled for horse clams. Tom grabbed the neck

while I dug. We skinned and pounded the neck, but it was still tough after

frying.

We also paddled out to the Limestone Islands where we found

a spectacular natural amphitheater ravine, focused on a huge spruce and with

the most luxurious moss we’d yet seen underfoot.

The next day we went on to Skedans, now another

Watchmen-protected village site. There were several standing totems, though not

as well preserved as at Ninstints. But there was one fallen one that was in

excellent condition, with a figure lying on its back with a R.I.P. bouquet of

salal in its hands. Sadly, loggers had stripped the forest to the very village

edge, and the logger and his wife lived in a trailer there, surrounded by oil

drums and refuse.

We stayed some distance to the south in a fisheries cabin.

We explored some nearby limestone caves that were quite extensive. Some of

these were wave-cut, but well above the normal water level. Far at the back was

a collection of large driftwood, attesting to the awesome size of winter storm

waves.

As we departed, a sailing catamaran came in to anchor at

Skedans. It had been built by Godfrey Stephens, a well-known sculptor from

Victoria. Many parts were salvaged from wrecks, and all of it was oiled with

pine tar rather than painted. It was about 35 feet long and 20 feet wide, with

lots of deck space. Space in the hulls was much more cramped. Godfrey had his

workshop in one hull and he and his companion Neva lived in the other. They

were exploring south, and we were able to give them pointers about places and

edible plants while they cooked us grilled cheese sandwiches on their little

wood range. I heard later that Godfrey cruised the BC coast for years in his

catamaran, until it broke up off the west coast of the Charlottes.

We headed north for our last campsite before Sandspit. We

found a large rushing stream to camp by, and took water from it to cook our

pasta dinner. We served it up and discovered that it was saltwater! The stream

was actually the reversing outlet from a tidal lagoon. Another lesson – taste

it first. After choking down our dinner, I walked a mile along abandoned

logging roads in this flat country looking for water, but found nothing other

than a few puddles.

We were on the water at 7 am for our run to Sandspit, since

the weather was rainy and a bit windy from the south. It was easy at first, but

freshened as we went along. We put up the sail and were pushed along so fast

that paddling made no difference. The seas built behind us and I shipped a few

into the cockpit, but we kept going. At the airport they told us that it had

been blowing over thirty knots. We rounded the spit in very shallow water and

landed at the airport only about 300 yards from our point of departure.

Since we were a day early, we stowed our gear at the

terminal and went into Queen Charlotte City for the night, taking the

barge-ferry across Skidegate Inlet. A nice re-entry – we met a lot of

interesting people there

living innovative lives, mainly on boats they had built or

maintained themselves.

That concludes the story. I haven’t been back to the south

Charlottes and probably won’t. By necessity, it is now vastly changed.

Fortunately the voracious logging that was churning southward along Moresby

Island has been stopped. The free-spirited community and their dwellings there

are all gone. The resurgence of BC’s First Nations’ sovereignty over their

cultural resources and the exponential growth of interest in visiting Gwaii

Haanas, mainly by kayak, have resulted in a climate of intense management. All

of that is necessary. I’m just glad to have seen it before it was.

1 comment:

I was glad to have this article sent to me just now so many years later now 2026 January the article written in 1974 and seeing the photograph taken by someone up the mast looking down on the deck. I really appreciate the photograph but the writing as kind as it was is quite inaccurate. The catamaran was 34 feet in length and 16 foot six wide not 20 feet and it did not break up off the West Coast of Haida Guaii The next year, my our Tilikum was born aboard in Tofino where We Neva and Me were building another Boat where We lived on the outside of Wickaninnish Island as said my catamaran did not break up it went on to have a tremendous life. Norman Abbey sailed her named TOMPATZ on a two year, tremendous voyage all the way to Panama and back to British Columbia and as far as I know that vessel went through about 12 different owners after me until she was poorly anchored and was smashed to pieces here in Victoria Godzes bay beach . This is why in my old age I must write a book to correct a lot of things like this I do thank the writer for the wonderful photograph. I wish He had more of them or some way of communicating with the writer if he's still alive.please contact godfreystephens@mac.com

Post a Comment