Posted with permission - This was originally posted at WashburneMarine.com by Randy Washburne - I have reformatted Randy's original post to work with my blog format. In so doing I have attempted to retain all of the original look and feel including punctuation.

Randel Washburne

Copyright 2007

Seymour Inlet Portage

Looking at a map, inland from the blunt wedge of Cape

Caution is a maze of waterways that incise for almost fifty miles into the

Coast Range, and all connected to the sea through quarter-mile wide Nakwakto

Rapids. There are a hundred miles of channels in here, some as much as a mile

wide, others much narrower, and running straight for ten or more miles. Connected

are as many more miles of brackish lagoons, where streams dilute the small

amount of salt that the flood tide brings to them. To the north are still more waterways

accessed from Smith Sound, and almost but not quite connecting to the central

bodies. To the south a similar one comes in from Drury and other inlets.

Its appearance suggests that its flat, with only slight

variations in elevation defining the edges between land and water. If you’re a

canoeist from the Midwest, you’d be reminded of the Boundary Waters area on the

Minnesota-Saskatchewan border, where chains of lakes are separated by gentle

hills allowing easy portages. It’s not like that.

The first time I ventured inland through Nakwakto Rapids, I

saw that steep mountainsides rose to a thousand feet or more directly from the

inland seas. No easy portages would be found here. Nevertheless, I was

intrigued with the idea of seeing this country without back-tracking by finding

a way across from the inlets to the south, mostly by paddle, and with as little

as possible overland by some means.

I asked around on north Vancouver Island, and learned that

the inland area had been extensively logged, and that most of the logs went out

from the central waterways to either Smith Sound or the southern inlets,

trucked over on local logging roads that connected them. Few went out through

Nakwakto, though log rafts were pulled through there on the short slacks,

mostly the produce of hand-loggers. So there had to be roads going where I wanted

to, and perhaps I could use them to carry my carted boat and gear across, or

cadge a ride with a logging vehicle. But I really didn’t know, and decide that

when a chance came to try it, I’d go on speculation and accept the uncertainty.

The opportunity came when I was building the Burnett Bay

cabin south of Cape Caution. Linda got a lift across Queen Charlotte Strait

from Port Hardy to the bay. After staying there for a week, we’d paddle back to

Port Hardy, drive south to Telegraph Cove in her car, and I’d find my way back

to Burnett Bay via some inland route, exiting at Nakwakto. I had no inkling of

the scale of what I was undertaking.

The territory through the Broughton Archipelago was familiar

until I passed Echo Bay and entered the labyrinth of passages leading north

along the widening Queen Charlotte Strait. I spent one night at what I believe

was a Kayak Bill camp. I came ashore in a small cove backed by an old midden –

mossy grass overhung by cedars. One of these had fallen to a low angle across

the grassy area. Clear plastic sheeting had been laid over it and secured with

rocks and driftwood into a tent. At the high end a rock fireplace had been

built with a driftwood chimney to carry the smoke away. Inside was a sleeping

area cushioned with dried ferns, next to a kneeling height table built from the

remains of a wooden pallet. A few things were stored in it, including .22

bullets. I’d heard that Bill lived on deer and seals.

I spent a very comfortable night there. I was determined to

leave no evidence of my visit – with one exception. The partly dis-constructed

pallet had some small nails protruding in toward the center. They weren’t

really in the way or a hazard to using the table, but they seemed offensive to

me in a way that they apparently were not to Bill. I got out my small vice

grips and pulled them all out and laid them in a neat row at the edge of the

table. My calling card. I never met Bill, so I have no idea about what he would

have thought upon kneeling at his little table.

I moved on to Sullivan Bay. This small harbor, with a resort

café and store along its boardwalk, had several yachts anchored. They wait here

for the window of opportunity to cross the dreaded Queen Charlotte Sound, for them

twenty or more miles of open coast with no refuge before Smith Sound. (Not so

for kayaks, which find good landings and camping every few miles.) This would

be my last chance to acquire anything before returning to Port Hardy, so I

bought a six-pack of beer.

Continuing north, I entered the unknown. My intended route

was into Drury Inlet, where successive narrows lead to possible overland

connections. I had some hearsay evidence that there might be a road from its

upper reaches into Seymour Inlet. Or, failing that, there was Lee Lake, which

almost spanned the distance to a lagoon connecting to the inlet. Failing these,

I’d just have to paddle back out, and continue up Queen Charlotte Strait. Knowing

my inclinations, that option was unlikely.

In early evening I entered Drury Inlet and started looking

for a campsite, which were typically sparse for this country. In Jennis Bay I

saw a floating logging camp where I though I might glean some information about

my intended route and possible campsites. I headed for one float where

convivial laughter emanated from what appeared to be the mess hall. A friendly

fellow came out to greet me as I tied up and invited me in.

Six men were sitting inside, relaxing with what was

apparently not the first of several post-work beers. “Hi, I’m Randy,” I said.

One of the celebrants replied, “I’ll be you are, sitting in a kayak all day!”

That brought guffaws from two companions and embarrassed grins from others who

had perhaps come more recently to the assault on the beer supply. No ill will

was intended, and after recovering, I took no offense. After all, this was

Canada where, like Britain and Australia, my name is an adjective. In fact,

that particular individual was the most helpful and supportive of what I was

trying to do.

Yes, there was a road to Seymour Inlet at the head of

Actaeon Sound. But, it was twenty miles long, went over a low pass, and was

washed out in two places. That dashed any hope of catching a ride on a logging

truck. Towing my boat on its cart for twenty miles of rough road would be a

competition between whether the cart, the boat, or myself would become damaged

to the point of unserviceability, and might take days or even a week!

So what about Lee Lake? They agreed amongst themselves that

they’d heard there was an old road up to the lake, and that it would be much

shorter, but had no idea how hard it would be to get from the lake down to the lagoon.

There was a hand-logger based in Creasy Bay where the road started, and perhaps

he might know more.

Thanking them for this invaluable local knowledge, I asked

if they knew of a campsite anywhere nearby. One of the people was a quiet

bearded man who turned out to be the camp caretaker. He had a whole house on a neighboring

log float, and invited me to stay there. Grateful that I would be relieved of

the chore of carrying the boat and all the gear above the tide line and setting

up my tent, I paddled around to his dock. All I had to do was tie up and bring

a few things inside.

Yet I was sorry I did. This turned out to be the most

slothful individual I’ve ever met. For some reason there was no water supply

hooked up to the house. The kitchen was piled high with dirty dishes, opened

cans, and half-eaten food. Since the toilet (which vented directly to the salt

chuck below) had to be flushed by bucket, he only flushed once every few days.

In light of these amenities, I decided to pitch my tent outside on the dock, claiming

(not untruthfully) that I slept much better in open air. I did manage to clear

a small corner of his table to cook my dinner. I offered him one of my beers,

but a bit uncomfortably he said he didn’t drink. I was unable to find out much

about this man, and truthfully didn’t want to.

In the morning I made as early a departure as gracefully

possible and continued into the inlet, and into the narrow winding stricture of

Actress Pass (Snake Pass to the loggers). The current picked up to a knot or

so, making me wonder about how many logs they were able to haul out via this route

from Actaeon Sound.

By early afternoon, I came to Creasy Bay where I’d been told

to look for the way to Lee Lake. An old ferry-like hulk was tied up there, and

a floatplane was letting off a passenger just as I arrived. It was good timing

– he was the hand-logger, Gil, just returning from shopping in Port McNeal, and

had been away for a week.

He invited me in for a cup of coffee. His vessel was

actually an old ferry (Stuart Island, I think), which had also been used in the

sealing trade in Alaska. In the kitchen (not “galley” since inside this was

more house than boat), he found no water in the tap, so I volunteered to do my

duty of following the plastic hose up the hill to put the upper end back under

the rock in little pool in a stream while Gil unpacked.

Gil told me that there really was a road up to the lake, and

that he would even drive me up there! Our transport was a decrepit VW bus,

who’s license tags had last been renewed eight years before. That was the last

year it had experienced third or fourth gear either, he said. The lower two and

reverse where more than enough out here. Most of the windows and the back door

had been removed. My boat went into the back door opening and forward so that

the bow lay on the floor between the front seats.

The old bus was likely the only vehicle to travel this old

road to Lee Lake in recent years. It was covered with leaves and small logs

that we bounced right over. It climbed steadily for the three miles it took to

get there. Not a good sign – I was in for a wild ride back to sea level,

however that would happen. We arrived at the south shore, and I saw that Lee

Lake was not a pristine jewel. The area had been clearcut about fifteen years

before, and recovery had been slow and uneven. Discarded logs lay everywhere

and floating ones crowded the shorelines. One of Gil’s reasons for coming up

was to bring down some pieces for firewood. I helped him load up, we shook

hands, and suddenly I was alone in the middle of no where.

I paddled to the north end of the lake, camped, and climbed

a small hill after dinner where I could look out to the north. The lagoons

wound invitingly into the distance through foothills and minor peaks, toward

Seymour Inlet beyond. A pretty sight, but from an elevated perspective that is

alarming if you plan to get there in a boat.

Thankfully, the next day was clear and warm. I paddled south

along the western shore to find the outlet. A shallow log-choked waterway would

through the trees, and I started in, climbing out to slide the kayak over a log

or two, and then back in to paddle a hundred feet or so before the next

barrier. The logs became thicker, and the water narrowed into a stream that was

now flowing steadily. But ahead it dropped away, leaving a clear view of the

distant hills beyond my destination, Nanahlmai Lagoon.

My waterborne progress was clearly done. I would need to

find a way to portage. Walking ahead, I found the stream dropped into a

rock-walled canyon. Beyond, about a half mile distant and several hundred feet below,

sun light sparkled on the surface of the lagoon. I knew I would not be paddling

on it today, and probably not tomorrow either.

This would take two stages. The first would be to haul my

gear, paddles, and anything else I could remove from the kayak down to the

lagoon and set up camp. The second would be the boat itself, which due to the sheer-sided

canyon and numerous fallen trees in it would be the most daunting challenge.

I had a large back-pack dry bag, which I would stuff with as

much as I could, leaving my arms free, as I’d surely need them. Down I went

along side the plunging stream. At one point there were sheer walls on both sides

of the rushing water. I found some footholds for a way, then had to step into

the stream, well over the tops of my rubber boots, and continue edging along.

At one point I lost my footing and went in chest-deep with still no bottom,

stopped only by grabbing the rock from being driven deeper by my heavy pack

(which I had thankfully closed tightly). This was the only route – I’d just

have to be careful here on the next trips, and there would be many.

Then the canyon opened up a little and I was able to climb

further down. But I could see that I needed to get to the other side, so I used

a jack-strawed pile of downed trees to cross about thirty feet above the water,

not really so bad, since I figured I could grab other logs if I fell off, or

hoped so.

The last part was easy – just finding a way through the

brush and into the forest by the lagoon. It led me directly to a good campsite

and launch point. Old cable and bottles indicated this had been used by the

loggers decades before. It was also popular with bears – the trees were heavily

clawed and scat was abundant. I unloaded and went back. Any time I was in this

lower part of the route I kept up a constant loud serenade for the bears and my

own confidence. “Hey bears! Comin’ through!” A few marching songs from my old

army days also filled the bill, and I think I invented some specialized verses

for bears that I’ve unfortunately forgotten. It worked, and none appeared.

It took five trips to bring everything down to the lagoon. I

kept going without breaks and didn’t finish until 9:30 pm. There were no

mishaps, and I figured out how to edge along the rock face without going under

water. I was very tired. After a high-carbohydrate dinner, I crawled into my

tent. I didn’t sleep well, partly due to my location in a bear congregation

area. Mostly, I was worried about tomorrow, whether I could finish this, and really

had no idea about how I could get the boat down here without damaging it or

myself. If I couldn’t, I’d have an even harder job dragging everything back to

the lake and then a walk out to beg another ride from Gil, if he was even

there. And, if I should get hurt, it would be way too late by the time anyone

figured out I needed a rescue or even where to look. I was truly on my own.

In the morning, thankfully another sunny one, I packed

several lengths of rope, my folding pruning saw, water, and lunch, and a small

tarp for emergency shelter into my back pack dry bag. Up with the kayak again,

I removed the rudder and duct taped around the exposed cables to protect them

from snagging on brush.

The way down the canyon was clearly impossible. I’d never be

able to carry or push the boat down the rocky falls without damage, and getting

it across the high jumble of logs was too daunting. So it would have to be up the

steep side to the flatter hillsides another hundred feet above, and trust that

there would be a way down through the old clearcuts from up there. This incline

was too vertical to walk up, but there were trees and rocks here and there to

grab. But how would I do that and carry the boat?

The solution was to climb up to the limit of my longest rope

(about fifty feet), tie it off to a tree, and then attach the boat’s bow line

to it with a prussic knot, a sliding hitch used by climbers to ascend ropes.

Then I climbed up to a point where I could hang on with an arm looped around a

tree, pull the boat up by the bow line, and slide the hitch up the fixed rope

as far as I could. Then climb up some more and repeat. By midway, each anchor point

might only net a foot or two of progress for the kayak. The young cedars now

became so thick that several times I had to use the pruning saw to cut a few to

make a space wide enough for the hull to pass through. The top was steepest,

semi-cliffs that required re-positioning the rope and careful work to hoist the

boat without falling. I was now well above the level of Lee Lake.

It seemed an impossible job, and I really wasn’t sure I’d

make it. It was the greatest challenge of will and perseverance I’d ever faced.

I encouraged and cajoled myself. Don’t stop, it won’t get done standing still.

Just think about the short-term and what’s to be done next. Think about Tristan

Jones pulling his sailboat through sixteen miles of the Mata Groso swamp.

After three hours, I came out onto a more open hillside at

the lip of the canyon. I sat on a stump with a sweeping view, at lunch, and

felt encouraged that the worst was over. In fact, it was. I was now able to

slide my boat down the gentle slope with only occasional need to saw out

obstructions. Then the hillside dropped more steeply, so I tied the rope to the

stern, aimed the bow downhill, and gave it a push. It slithered down and out of

sight into the dog-haired little trees, its progress continuing and controlled

by the paid-out rope. At rope’s end, I stopped it, followed it down, re-aimed,

and pushed off again. It was so easy I had a chuckle watching it disappear into

the brush, while just trusting that it wasn’t about to drop over an invisible

cliff. But there were none, and the boat and I emerged into the older forest

below. Now shouting a triumphant greeting to the bears, I towed it through the

ferns and salal and over old mossy logs to my camp, arriving about 4:30. I

rested easy that evening – the remainder of this would just be fun.

At the water’s edge, I could see that the tidal range of

Nanahlmai Lagoon was only a foot or so. So little sea water passed through the

successive narrows from the ocean that its flow had negligible effect on the

lagoon’s level. The first such constriction was at Nakwakto Rapids, which reduced

the eighteen foot range on the Pacific

to about six feet on Seymour Inlet. Because of that, these

inland waterways kept a level somewhere between the extremes of the larger

outside waterway, and the slacks in the connecting narrows occur somewhere around

mid-tide when the levels equalize. It is an excellent example of how tide

tables are a poor predictor or currents.

There would be a high tide on the Pacific mid-morning, so I

hoped to pick up and ebb current on the way out and try to make it through

Nakwakto before the next rising tide brought the flood current.

It was truly a joy to be afloat again and sliding along so

easily, covering in the first fifteen minutes the distance of the last two

days’ hard work. The weather was overcast but windless and peaceful.

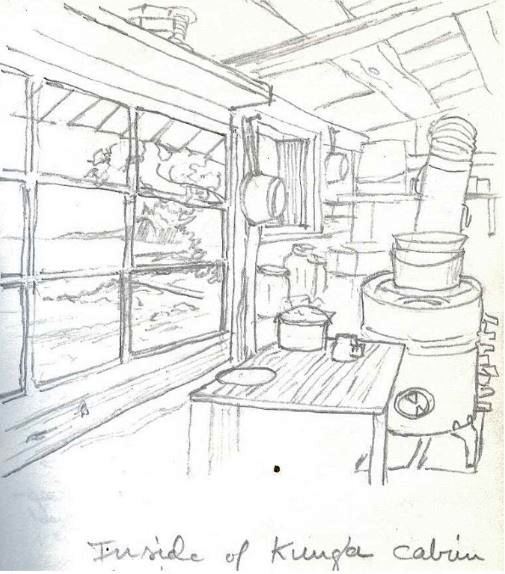

I came to the first narrows and picked up a gentle current.

A floathouse on a log raft was teathered with cables along the shore here. It

was the mobile home of hand-loggers, and I saw them working on shore a mile or

so beyond. The waterway opened up as I came out into Seymour Inlet, which lead

eastinto the coast range as far as I could see. I turned west, continuing on

for several hours. There was more evidence of logging now.

At the junction with Nugent Sound I stopped at Holmes Point

to see the old native village site. There was beautiful lush forest and an open

bramble-meadow that apparently covered the remains of long-house pits.

Now came Nakwakto. A logger’s skiff passed me and sped out

through the ebbing narrows. If he could do it, so could I, since it wasn’t a

particularly big exchange. I stayed to the south side of Turret Rock, rode down

the fast sluice to the standing waves where the water slowed after the rapids –

a little splashing but no trouble. The current was still going my way, so I

pushed on into Slingsby Channel.

A mile farther on a hand-logger’s skiff was tied to shore

and a chainsaw was running up the hill, though I couldn’t see the operator

through the trees. So I waited to see what would happen. Soon, a big cedar

slowly tipped out from the forest and plunged down the hillside into the water.

The still-unseen logger shut off the saw, and in the silence, I clapped. Then I

moved on, leaving him to wonder about the mysterious applause.

There was one last ride through the last of the ebb current

at Slingsby Narrows, and I turned north along the Pacific shore toward Burnett

Bay, thinking that I had no regrets about this adventure. It was out of my

system now - I’d seen that country, knew that there was no kayaker’s Northwest

Passage back there. It could be done, but I wouldn’t again, nor recommend it to

anyone else.